|

|

|

János Molnár: Foreign Correspondents in the 1956 Hungarian Revolution

Introduction

Hungary became the centre of world press attention when the uprising broke out unexpectedly on October 23, 1956. Events in Hungary became the lead story in the next few days. But on October 29, attention was distracted by the outbreak of the Suez conflict, though Hungarian developments remained prominent for several more weeks and months. Before the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution, analysts had been more interested in events in Poland, where Władisław Gomułka had been chosen to head the communist party over the heads of the Soviet leaders, causing predictable tension between the two countries. As late as October 22, several dozen Hungarian journalists had also been sent out to Warsaw. The world press was quite unprepared for what would happen in Budapest, with very few journalists present there. After October 23, the number grew by the day, reaching a peak of about 150

.

Most of the foreign journalists arrived in Hungary around October 27-8 or a few days later. The majority represented the press in capitalist countries; those from the Eastern Bloc came mainly from Poland and Yugoslavia. The Soviet invasion on November 4 meant that Budapest counted as a war zone and it was impossible to leave for several days, but most correspondents departed between November 8 and 11 as hostilities died down. The revolution had failed, the street fighting was over, and the sensation had come to an end. A few journalists stayed on, but the Hungarian authorities were reluctant to extend their permits. By the early days of 1957, the last Western journalists had been pressured to leave, apart from a single Reuters correspondent.

This study deals mainly with Western correspondents. Most of those from the Eastern Bloc wrote anonymously and their work did not reflect their personal opinions. The press in most communist countries took over verbatim reports of the official Soviet news agency TASS or Pravda, central daily paper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Journalists elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc took a similar line, branding events in Hungary as counter-revolutionary. Not so the Polish or Yugoslav journalists, though. The former rejoiced openly. Yugoslav reports were also enthusiastic until the official Yugoslav view emerged in early November.

The study aims mainly to outline who the foreign journalists in Hungary were during and after the revolution, and what papers they worked for, to sketch the conditions in which they worked, and to show how they were treated by the Hungarian authorities after the revolution was over. It does not look at what the foreign correspondents wrote about the revolution.

Antecedents

Correspondents of Western news agencies had been successively expelled from Hungary since the Stalinist system began to consolidate at the end of the 1940s. Life for Hungarians working for them became impossible and some were imprisoned. So for a good while, no Western papers and news agencies had had permanent correspondents in Budapest.

The exceptions were a married couple: Endre Marton

and Ilona Marton

, reporting for the US agencies Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI) respectively. The illogicality of the system appears in the fact that they had managed to work relatively undisturbed for their American customers throughout the period when Hungary was gripped by spy hysteria, only to be arrested on spying charges in 1955, after the détente.

|

| István Rusznyák, György Lukács, Imre Komor and Imre Nagy in the lobby of the Parliament during the session in 1954 |

|

|

Apart from the reports of the Hungarian news agency MTI, hardly more than official communiqués, the Martons were the only source of fresh news from Hungary that the Western media had. They, through AP and UPI, supplied the news to practically all the Western agencies. As for the foreign-policy journalists specializing in the Eastern Bloc, having been expelled from the people's democracies, they sat in Vienna trying to keep up with events behind the Iron Curtain. It was most important to their credibility that they should visit communist countries such as Hungary from time to time, but the bureaucratic barriers and controls had been formidable in 1949-53.

The latter year brought political détente associated with the name of Imre Nagy, which heightened the Western press interest in Hungary, and the number of visiting journalists increased. With the Martons in prison, there were no permanent correspondents in Budapest, but the visitors helped to fill the gap. So several foreign journalists reporting on the events in October were not visiting the country for the first time. Veteran John MacCormac

, for instance, Vienna correspondent of The New York Times, was a well-known figure, having been to Hungary several times. He had come in the spring with Simon Bourgin

, Vienna correspondent of Time magazine, and spent a few days in the Hungarian capital in August.

|

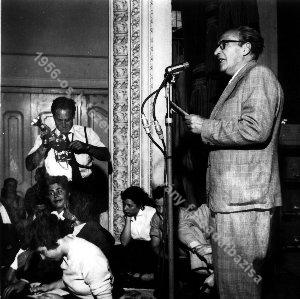

| Audience at press debate of Petőfi Circle |

|

| Sajtóvita -* |

|

|

Leslie B. Bain

, a US journalist of Irish and Hungarian extraction who spoke Hungarian and was conversant with the region, had been in Hungary several times in 1956, gathering material for a book on the countries of the Eastern Bloc. Bain worked for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA), submitting articles mainly to the New York Reporter.

The first day (October 23)

Few of the 150 or so foreign correspondents in Hungary a week after the revolution broke out had actually witnessed events from the start. Most had been drawn to Hungary by the initial sensation of revolution breaking out.

It usually took a few days to reach the location. Entry was impeded by the collapse of transportation and anarchy caused by the conditions of war. A visa was still required up to October 28-9 and many correspondents spent days waiting on the border.

But luck or a good nose meant there were already half a dozen Western journalists in Hungary on October 23. There were three Hungarian citizens living in Budapest at the time who had worked for Western news agencies: the Martons, mentioned earlier, and Aurél Varannai

. Working for "imperialist" news agencies in the Rákosi period of Hungarian Stalinism was not free of risk. All three had been through troubled years of imprisonment and internal exile. Nonetheless, they set to work again in October.

Varannai had worked for the British agency Reuters until 1948 and then been arrested. He had been in prison and out in the following years, but he had not been able to work again. Endre Marton, when arrested on spying charges at the beginning of 1955, was sentenced to six years imprisonment, but freed in August 1956. His wife Ilona had been released four months earlier

.

So Endre Marton and Aurél Varannai, released in September, were witnesses to the events of the October revolution from the outset and able to send numerous reports to the West. Ilona Marton, on the other hand, had travelled to the UPI office in Vienna a few days before the revolution broke out and only returned to Budapest on October 29.

About midday on October 23, Varannai ran into MacCormac, head of the New York Times Vienna office, at the Duna Hotel. He had had the remarkable luck or acumen to be in Budapest with his wife in the second half of October. Varannai drew the American journalist's attention to the student demonstration due that afternoon. MacCormac immediately asked his Hungarian colleague to report for the New York Times, and he agreed.

Also in Budapest in 1956 was a 35-year-old British communist, Charlie Coutts

, working at the Budapest headquarters of a communist front organization, the World Federation of Democratic Youth. Coutts, apart from copy-editing English texts, wrote for the British communist Daily Worker. He attended the afternoon demonstration on October 23 and phoned in a report to his paper.

The first day was witnessed by other, non-resident correspondents who happened to be in Budapest. Leslie B. Bain had arrived from Paris on October 19, and following a tip from a Foreign Ministry official, travelled to Szeged, where an independent student body had formed on October 16, the Association of Hungarian University and College Students (MEFESZ). Bain attended the inaugural Szeged rally of MEFESZ and then drove up to Budapest on the 22nd with two student delegates from Szeged in his car

. On the evening of the 23rd, he saw the great statue of Stalin toppled. When they returned to the Radio building at 11 p.m., the Hungarian tanks had already appeared. Bain was still able to file his report of the extraordinary events at 1 a.m. at the Central Telegraph Office.

|

| Destroying the statue of Stalin: remnants of the statue |

|

| Hotel Duna |

|

|

Sefton Delmer

, correspondent of the Daily Express, only arrived in Budapest on the morning of the 23rd from Berlin. He was in the Duna Hotel during the day, and as an experienced journalist, paid close attention to the demonstrations and the unfolding uprising from that central position, where he could file his reports. But after midnight, the telephone lines to the West were cut and the hotel was isolated. The Duna on the Pest bank of the Danube was the usual base for foreign correspondents visiting Hungary-the sole survivor of a row of hotels on the Danube Corso destroyed in World War II.

Though it was in very poor condition, 90 per cent of the Western journalists stayed there during the revolution, although there was only a manual telephone handled by an operator.

Among the foreign journalists who reacted fastest to the events was the Italian Ilario Fiore

, special correspondent of Il Tempo and the only Italian journalist filing from Hungary at the time. On hearing news of the Budapest demonstrations, he caught a train from Vienna at 5.30 p.m. on October 23-practically the last train to arrive, just before midnight, at the Eastern terminus in Budapest. Fiore claimed to be the second journalist on the scene after Delmer, naming as the third Bruno Tedeschi of Il Giornale d'Italia and the fourth Barrett McGurn of the New York Herald Tribune.

Since nobody could be at all important places at once, the known correspondents worked together. Varannai was at the demonstration at the Petőfi statue in Március 15. tér, the advertised starting point on the Pest side. He gave "Revolution in Pest" as the title of the report he filed that afternoon to the Vienna office of the New York Times

Endre Marton went that day to the protest in Bem tér on the Buda side of the Danube, where stood the statue to General Józef Bem, the Polish hero of the 1848-9 Hungarian War of Independence. From there the crowd moved to the square before Parliament, where the speech by Imre Nagy was delivered. Marton then heard that the crowd wanted to topple the statue of Stalin and went to Sztálin tér in the car of a Hungarian journalist he knew. Both Marton and MacCormac had trouble making telephone contact that night. They were finally able to file their reports through the AP centre in Belgrade and a private telephone in Prague. By late evening on October 23, all telephone lines had been cut and they could not send any further news.

October 24-November 4

The number of foreign journalists steadily increased in the next few days. They drove enthusiastically about the city looking for scoops and historic moments and formed groups to visit the provinces. They crept on foot up to the firing line, trying to reach the action. They all tried to prepare exclusive reports for their papers. The first major item of news in the early days of the uprising was the massacre outside Parliament on October 25, when fire was opened on the assembled crowds from the rooftops, under circumstances that have never been clarified.

On that day, Thursday, MacCormac and Marton went to the American Legation in the morning and saw from the building in Szabadság tér how a large group of demonstrators and some Soviet tanks had passed into Kossuth tér, before Parliament. They followed, and they were under the arcade of the Agriculture Ministry, opposite Parliament, when the shooting suddenly started. The New York Times reported next day on a bloodbath with at least 60-70 victims. The shooting was also witnessed by Charlie Coutts, who was in the crowd. According to his report, which later featured in Peter Fryer's book as well, the shooting came from neighbouring rooftops, almost certainly from ÁVH (secret police) men

.

|

| Collecting dead bodies on Kossuth square after the fusillade in front of the Parliament |

|

|

On the same Thursday arrived Seymour Freidin

, correspondent of the great US popular paper the New York Post. Known to everybody as Sy, Freidin was accompanied by his wife. Another arrival was Gordon Shepherd

of the London Daily Telegraph, who visited the scene of the shooting at 3 p.m., by which time the dead had been carried away.

Noël Barber

, one of the fastest-moving and most venturesome of journalists, was still in London on the morning of October 25, organizing his journey by telephone. As an acquaintance of Prime Minister Imre Nagy, he received a visa immediately and flew to Vienna via Paris immediately. He hired a car at Vienna Airport, taking with him ten cartons of American cigarettes and two bottles of whisky for bribery purposes and his own consumption, and immediately sped towards Hungary. He crossed the border at 9.30 p.m. and continued to Budapest. There he became embroiled at the Chain Bridge in a gun battle between insurgents and Soviet tanks, and one Pest youth died in his arms

.

Peter Fryer

of the communist Daily Worker spent the night of October 26 in the waiting room at Hegyeshalom, the frontier railway station. The Austrian side of the border was full of British, German and Austrian correspondents who had no Hungarian visas, so that the Austrian border guards were not letting them across. Fryer, as correspondent of the British communist party paper and a regular London correspondent of the central Hungarian communist paper, Szabad Nép, had no trouble getting a visa, but all the more finding a car. According to his account, he was the first Western communist journalist on the scene.

While arranging matters at the Hungarian consulate, Fryer had run into Jeffrey Blyth of the British Daily Mail, who was just back from Egypt, where he had been reporting on the Suez Crisis. Blyth, who was acting as Noël Barber's liaison on the border, offered to take Fryer to the border, where Blyth's colleague was waiting to hand over copy for him to bring back to Vienna. Fryer went on from the border with a German Red Cross consignment of medicines for Mosonmagyaróvár.

Mosonmagyaróvár provided the next sensation for the journalists. On the day before Fryer's arrival, October 26, border guards had opened fire on demonstrators and killed more than 50 people. Many foreign journalists managed to arrive at the scene, as Mosonmagyaróvár is the first major town after the border. The dead were laid in state together, in public.

|

| Barrier is lifted in front of the transport of Red Cross at border crossing station at Kelénpatak-Sopron |

|

|

Fryer was shaken by the tragedy and swore he would only write the truth about the events. This would cause him much trouble later, as the Daily Worker was not wont to publish reports that conflicted with its own line. In the end, none of the reports Fryer sent to London was published.

At dawn on October 28, a plane from Warsaw carrying blood plasma from the Polish Red Cross arrived at Budaörs Aerodrome. It also carried two British former intelligence officers who were now journalists: Anthony Cavendish

, Warsaw correspondent of the British United Press, and Basil Davidson

of the London Daily Herald

.

Vittorio Mangili, a Milan staffer of the Italian radio RAI, organized his own trip to Hungary. He undertook to take medicines worth 4 million lira to Budapest for the Italian Red Cross. Arriving in Budapest on the 28th, he set up camp at the Duna Hotel, like the other correspondents. In order to send his reports, Mangili travelled daily between October 28 and 31 between Budapest and Vienna, setting out in the morning from Vienna and in the evening from Budapest, getting a lift on a vehicle. Aid consignments were arriving constantly and there was no difficulty about finding a suitable car.

Filing was one of the greatest difficulties faced by the correspondents. The long-distance telephone lines were not working and the news had to be sent out of the country by devious means. Some, like Noël Barber, drove from Budapest to the border to hand their reports over. Journalists with diplomatic connections tried to use the telecommunications available at foreign missions.

As Endre Marton wrote, "Connections were extremely irregular in the following weeks. Sometimes the telephone would miraculously start up again, other days I stumbled on a telex line, but most of my reports were taken out some Western colleague returning to Vienna, fed up with coping with dead telephone lines. There were also times when staff of the American Legation sent to Vienna handed in my reports at the AP offices there."

On October 28, Peter Howard, working for Reuters and for the Süddeutsche Zeitung in Munich, had some exciting adventures on a provincial trip. He had arrive in Győr by bus from Austria the day before and travelled on to Veszprém. There he had interviewed the head of the local national committee before turning back for Austria, presumably to file. The committee chief offered him a car and armed driver for the purpose. The weapon was certainly needed on the journey. While taking a short cut on a dirt road, they met a Russian soldier who immediately opened fire on the vehicle. Howard's driver reacted fast, shooting the soldier dead.

Other arrivals in Hungary on October 28 were Jean-Pierre Pedrazzini

and his colleague Paul Mathias, who was of Hungarian origin. They came to photograph the victims of the Mosonmagyaróvár shooting.

Noël Barber was back at the Austrian border on Sunday the 28th to hand over his copy before returning to the Duna Hotel in Budapest. That evening he toured the city with Sefton Delmer and Barber's Hungarian escort. They saw a Russian soldier in Szent István körút, near the Western railway terminus, but when they tried to pass him, he shot a volley into the car. It was lucky that the driver, Barber, was the only one of the three to be wounded. He was shot in the head but the wound was not dangerous. During the incident, the enraged Delmer jumped out of the car and went for the soldier with bare hands, but luckily he fired no more shots. They took the blood-soaked Barber to the British Legation-the first foreign journalist to be injured in the revolution

.

Russell Jones, roving reporter of United Press International, and Ilona Marton, arrived on October 29 by car from Vienna, where Ilona Marton had been monitoring Budapest broadcasts since the revolution broke out. The border was open. Foreigners no longer needed visas. They recounted that the roads were full of control points manned by insurgents or Soviets. They finally arrived in Budapest after several adventures.

That day the Suez war broke out, with its familiar foreign-policy consequences for the Hungarian Revolution. By next day, Hungary was no longer the top foreign story.

On Tuesday October 30, crowds laid siege to the Budapest communist party committee building in Köztársaság tér after a group of armed insurgents had fired on it. The building was taken after heavy fighting. The enraged crowd then lynched some of the defenders before the eyes of the press. This bloodshed became one of the most written about events of the revolution. By this time, Budapest was swarming with foreign journalist, several of whom were present at the siege. They included two Polish correspondents: Marian Bielicki of Po Prostu and Polish Radio, and Krzysztof Wolicki of Trybuna Ludu. Photographs were taken in the square by Mario de Biasi of the Italian magazine Epoca. The US journalist and photo reporter John Sadovy was also there. His series of shots of the executions appeared in a special edition of Life magazine in December and went round the world

.

|

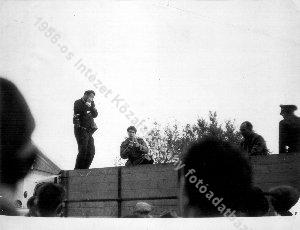

| French photographer, Jean-Pierre Pedrazzini working |

|

| French photographer, Jean-Pierre Pedrazzini in hospital |

|

|

Tim Foote, another Life photo reporter at the siege, received a light injury in the hand. Also in the square were Jean-Pierre Pedrazzini and Paul Mathias, both photographers with Paris Match. During the firing, Pedrazzini received a whole volley in his body and leg, probably from a tank arriving in the square. Both the injured press men were taken to a nearby hospital. Pedrazzini underwent immediate surgery, but his injuries were hopeless. The dying man was flown out on an Austrian ambulance plane to Paris on November 3. He died aged 29 on November 7, the one foreign press victim of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

Lajos Léderer

accompanied by journalist Peter Strasser arrived in Budapest on the evening of October 31. Léderer had been travelling in Western Hungary beforehand, making reports on the insurgents. For their Budapest trip, the two men had two students with machine guns as bodyguards, which made it easier to get through the insurgents' road blocks. When they arrived in Budapest, several other armed young men joined them, and according to Léderer, they had quite a private army by the end.

An Italian convoy also set out from Vienna to Budapest on October 31, bringing with it the French journalist Dominique Auclere of Le Figaro, who had wasted several days in Vienna without a visa. Another arrival in Budapest on that day was Thomas Schreiber of Le Monde, who was of Hungarian origin. He was brought across from Vienna with another journalist by car by Turbet-Delof, director of the French Cultural Institute. They had no Hungarian visas

.

Indro Montanelli

, correspondent of Corriere della Sera, and Matteo Matteotti, Italian socialist MP and journalist, also arrived in Hungary on that day by car. Next day, November 1, they set off back to Austria, but did not leave the country as they were stopped by Soviet troops a few miles short of the border. Seeing the tanks, they decided to return to Budapest.

On November 1, Bruno Tedeschi of Il Giornale d'Italia in Rome managed to interview János Kádár, before he went over to the Soviet side

.

The only news conference ever held by the Imre Nagy government took place in Parliament in the late afternoon of November 3.

Nagy was represented by the state ministers Géza Losonczy and Zoltán Tildy. About 150 Hungarian and foreign journalists appeared. Among them was Endre Marton, finding it strange to attend a free, Western-type news conference for the first time since 1947.

Aurél Varannai sat between MacCormac and Léderer

. There were crowds of Hungarian journalists in the room, but he did not know them; they belonged to a younger generation. Among them was Endre Gömöri of Hungarian Radio, who translated what was said into English for Seymour Freidin.

The conference progressed fitfully as nobody had thought to provide the right interpreters. An argument broke out meanwhile between Lajos Léderer of the London Observer and Iván Boldizsár, who was translating into German and English. Boldizsár had earlier given false testimony against Aurél Varannai in that journalist's trial.

Early days of the Soviet invasion

Soviet troops attacked Budapest at dawn on November 4, with the purpose of crushing the revolution. After the attack, most of the foreign journalists sought refuge in their own diplomatic missions. Most of the family members of diplomats and other Western representative offices were sent out to Austria in convoys in the following days. In Budapest, refuge in diplomatic missions had to be given mainly to correspondents and to the families of Hungarian employees in the missions.

|

| Russian tanks in front of the Hungarian Parliament |

|

| Tanks and passers-by |

|

|

The American Legation prepared after the attack to give refuge to its citizens. A list was made of eight American journalists thought to be in Budapest and information on this was sent to Washington headquarters

. That evening at eight, the legation sent a telex to Washington saying there were several American correspondents in the building. Among those given refuge were Endre Marton and his wife, as accredited Budapest correspondents of American news agencies, and their daughters. The legation had wanted for policy reasons to accept only American citizens, but an exception was made for the Martons when other journalists intervened. According to Marton's memoirs, refuge was given only to the American correspondents, to a West German technician of CBS and his family, and to Cardinal József Mindszenty, primate of the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary. (Mindszenty remained until 1971.)

The American journalists and the Martons were guests of the legation for a week. It was not possible to make international calls from the building, but the State Department in Washington managed to restore links, and the correspondents were given leave to send news summaries to the main US newspapers and agencies.

The first to venture out and look round after the fighting that broke out at dawn were Eldon Griffiths

of Newsweek and a British journalist. Griffiths és Sefton Delmer went to look round Parliament a few days later and tried to enter the nearby Soviet headquarters, where they were almost arrested. Another group of American correspondents headed by Endre Marton, MacCormac and Russell Jones first left the legation building on November 6 and walked down to the Duna Hotel.

The American journalists eventually left the legation for Vienna in a convoy on November 10. Only Ronald Farquhart of Reuters, Russell Jones of UPI and MacCormac of the New York Times remained. Marton Endre and his wife and two daughters returned together to the Buda home

.

|

| The Hungarian flag at the frontier of Hungary and Austria |

|

| Refugees at the Hungarian-Austrian frontier |

|

|

Sefton Delmer of the Daily Express moved into the British legation building in the days after October 23. Delmer tried to persuade the head of mission, Leslie Fry, to allow the telecommunications system in the building to be used for correspondents' reports. For a short while, refuge was given in the building to Edith Bone, former correspondent of the British communist Daily Worker. A former doctor of Hungarian origin, Bone had been arrested by the ÁVH as a British spy, during a visit to Hungary in October 1949. She had spent seven years' in prison, mainly in solitary confinement, before being freed by insurgents on November 1. She was 68 years old

.

Some British correspondents tried to leave the country before the Soviet attack. A few of them are thought to have set out for Suez. On November 3, Jeffrey Blyth of the Daily Mail telephoned from the border to the British legation in Budapest, reporting that convoys of Russian troops moving towards Austria had detained him. According to information he obtained from the Russian officers, it was likely they could be held there for two or three months.

The injured Noël Barber and his escort set out for Austria on Saturday in a car with a shattered windscreen, but they were also stopped by Soviet tanks just before the border. They had to stay at Hegyeshalom for 14 hours, within sight of the border. The Soviets were firm and unruffled by the many protesting foreigners

. Among the other Britons held at the border that day were Gray of ITN, Sefton Delmer of the Daily Express, and Anthony Terry of the Sunday Times and his wife

.

Anthony Cavendish and Basil Davidson took refuge in the British Legation on November 4, after the bombardment began. After a few days', Cavendish set off on November 8 by car to the Czechoslovak border, taking Davidson of the London Daily Herald and Ernest Leiser of CBS

. Before setting out, they approached Soviet Ambassador Yuri Andropov

for safe passage, but he dismissed this as unnecessary. However, they were turned back at the Czechoslovak border for want of valid visas. Next day, they continued west along the Hungarian shore of the Danube, only to be stopped and held at a Soviet control point in Győr. Their car was confiscated, with all their notes and films, and they were kept in a hotel for three days. Cavendish spent two hours haranguing two KGB majors what he had seen and who he had met in Budapest. Finally, on the third day, they were given back their car and possessions and reached Vienna safely

.

Some 40 people took refuge in the French Legation on November 4, mostly journalists of various nationalities

. There was not enough food, especially bread, for them in the building, but the Austrian Red Cross brought supplies a couple of days later. Thirteen Austrian reporters set out for Austria on November 8 and 30 others joined a convoy next day.

Not all journalists chose to seek diplomatic protection. Three Frenchmen-André Teillet, Alain de Sedouy and François de Geoffre-and a Hungarian woman of French nationality remained in the Duna Hotel. Later Sedouy és Geoffre wrote a book about their experiences in the revolution

.

The journalists sheltering in the diplomatic missions were not usually allowed to move freely round the city for security reasons. Vittorio Mangili of RAI was the single exception. He undertook to walk in every day from the Italian mission, further from the centre, to forward reports from the more central British Legation to London. (Presumably the Italian mission had no contacts with Rome at the time.) Having undertaken that, he was freer to walk about the city and tried to capture some more important moments. He was the bravest of the Italians, walking the streets with his Hungarian escort, by the name of Lajos, and filming with a simple spring-mechanism camera. His stock of film was very meagre and so he had to be selective. This exceptional footage found its way to the United Nations. According to Indro Montanelli, his colleague did hair-raising things during the revolution: travelling in the same car with a messenger from the insurgents, jumping on an artilleryman handling a gun at the Eastern terminus, witnessing the examination of a Russian major, etc

.

Conditions for those crowded into the diplomatic missions worsened every day. The journalists felt like prisoners and wanted to get out.

Michel Gordey

of Paris Soir, who spoke Russian perfectly, headed a group of journalists who tried to obtain free passage from the Soviet headquarters on November 8. The Russians promised everything, but they only issued the necessary stamped papers on November 9. And the permit proved insufficient, because the cars leaving Budapest were stopped at the first checkpoint

.

The Italian journalists finally received exit permits through Alberto Jacoviello

. He was offered a permit by the Soviet city governor because he wrote for a communist paper, l'Unita. Jacoviello refused to go unless his colleagues were allowed out as well, and the Russians eventually agreed. So a dozen Italian journalists left Budapest in three cars with Italian number plates on November 10 (or 11)

. They were stopped by tanks near Győr, and as the order from headquarters to allow them through had not reached them, they were arrested. They spent the night at a Soviet camp in a nearby hospital and proceeded next day. All the Italian journalists except Mangili probably left in this group, including Luigi Fossati of the socialist paper Avanti, who also wrote a book about the Hungarian Revolution

.

Vittorio Mangili set out next day, Sunday, November 11, towards Austria in a convoy of journalists, having received permits to leave from the Soviet military authorities. The conditions were strict: the driver of each car had to feature on the list of those carried. Cars of the same nationality had to travel together, and newspapers, photos or information materials could not be taken. Mangili travelled in a car full of French. They were stopped at seven Soviet checkpoints between Budapest and the border, yet managed to smuggle out film footage made during the last days of the revolution

.

Leslie B. Bain left for Austria on November 10, taking with him Dr Egon Turcsányi, secretary to Cardinal Mindszenty. They were stopped by ostensible secret servicemen at a checkpoint at Tatabánya, where the elderly priest was pulled out and arrested. (He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1958.) Bain was then able to leave the country without further ado

.

Mid-November onwards

All but a handful of the correspondents had left Hungary by mid-November. The fighting was over and the fate of the revolution seemed clear, so that press interest waned. But the journalists who had been in Budapest continued to write articles about what they had seen. Many of them spent a longer or shorter period in Vienna, observing events from there, or following up the fate of the many refugees.

The three Hungarian correspondents, Varannai and the Martons, continued their work doggedly. Among others who remained were John MacCormac of the New York Times, Russell Jones of UPI, and Ronald Farquhart of Reuters. Apart from blazoning news to the world of the Soviet aggression and crushing of the revolution, the correspondents played some important mediating roles after November 4.

Many people in Hungary kept themselves informed by listening in to Hungarian-language broadcasts from the West. These relied on fresh news from Budapest sent by the foreign journalists still present.

Western diplomats tried hard to ensure the correspondents could remain. The tactic of the new Hungarian government, however, was to try to get rid of the journalists, whom it saw as too "enthusiastic".

So foreign journalists would often be held for a short while by the Soviet occupation forces or the Hungarian authorities. The one held longest-almost seven weeks-was US photo reporter Georgette Dicky Chapelle

. The 37-year-old had arrived in Austria on November 15, and as a staff member of the International Rescue Committee, visited many of the refugee camps, interviewing and photographic Hungarian refugees. She wanted to visit Hungary as well and went to her embassy in Vienna to validate her American passport for a single visit. Perhaps visa difficulties prompted her to cross the border illegally with a Hungarian escort, at dawn on December 6. She was taken into custody by Hungarian border guards only 10 km from the Austro-Hungarian border.

Chapelle's disappearance prompted the American Legation in Budapest to send a note to the Hungarian Foreign Ministry on December 15, enquiring where she was. The Hungarian authorities failed to react to several US memos, which prompted the Americans to state that according to their information, Mrs Chapelle was being held in Cell 504 on the fifth floor of the Military Courthouse in Budapest's Fő utca. Even then, the Hungarian Foreign Ministry refused even to admit on January 19 that they knew she had been arrested. Matters were speeded up eventually when the American Legation broke with diplomatic practice and obtained a permit directly from the Chief Prosecutor's Office to visit the prisoner. The American consul in Budapest, accompanied by a lawyer, then managed to see Chapelle in her Fő utca cell. She was then brought quickly to trial, and on January 26, deported with immediate effect for having entered the country illegally

.

Though Soviet forces had crushed the revolution, Western interest in Hungarian events was still strong in November and December. The press strove hard to send their staff back in to obtain fresh information.

One of the last '56 correspondents to remain in the country was Russell Jones, who filed to UPI by phone. He reported on the women's demonstration in Hősök tere on December 4 and was expelled from the country next day. His articles on '56 won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1957.

Two Italian journalists, Egisto Corradi and Alberto Cavallari of Corriere della Sera, managed to get back into Hungary in the latter half of December 1956

. Richard Kasischke, head of the AP bureau in Vienna, also arrived and stayed in Budapest until the second half of January.

The three Hungarian correspondents remained active until December. Then Endre and Ilona Marton, seeing the reprisals that were taking place, decided to leave. The Hungarian authorities implicitly concurred in this by issuing them an exit visa when it was clear they would not return. They left the country on January 16, 1957 with their children, in a car from the US Legation. Aurél Varannai remained in Hungary despite the persuasions of John MacCormac. He retired from journalism and rode out the period of reprisals at his house in Balatonszemes. In the event, the Hungarian authorities never harassed him for his activity in the revolution. After his exile from the capital, he returned to work as an editor for the scholarly publishing enterprise Akadémiai Kiadó and do research into Anglo-Hungarian literary connections

.

John MacCormac was among the last foreign correspondents to leave Hungary. He was expelled on January 10, 1957, being given only six hours to cross the Austrian border.

As most Western correspondents were departing in mid-November, Soviet journalists began to arrive. Hitherto, local coverage on Moscow Radio had been confined to reports from enraged ostensible Soviet tourists. The task of those arriving now was not primarily to keep Soviet readers and listeners informed, but to expand on the purported counter-revolutionary and fascist character of the events in Hungary.

A reporting tour of Hungary began in mid-November for Mikhail Odinets and P. Yefimov, whose first piece in Pravda on November 17 and was followed by another every two days. A. Romanov of Lityeraturnaya Gazeta also arrived in the second half of November, followed in early December by A. Kurov, as Hungary correspondent of the foreign-policy paper Novaya Vremya. The work of this group was encapsulated at the end of 1956 in a four-author book on the Hungarian "counter-revolution", published by Pravda

.

The Western communist papers also sent journalists to Budapest after the fighting had died down. Peter Fryer left Hungary on November 11, disillusioned with communism. He had been dismissed as the Daily Worker correspondent for the sympathy he had shown for the revolution and his reports had not been published. He was replaced by Sam Russell, hitherto the paper's Moscow correspondent. The 29-year-old Fryer was leaving his paper after 13 years. He soon resigned from the British communist party as well, and then published a book on his experiences

.

The French communist party l'Humanité sent its editor-in-chief, André Stil, to Hungary on November 12. He would soon write a book entitled I Came to Budapest, following the official Moscow line closely

.

There was much Western media interest after the revolution in the new communist leader, János Kádár. The Hungarian Foreign Ministry was inundated with requests for interviews, but these were refused.

|

| Kádár János hazaérkezik Moszkvából a Ferihegyi repülőtéren -* |

|

|

The Hungarian authorities in November 1956 sought to eliminate Western correspondents from the country. Their activity, according to the Foreign Ministry, was not limited to journalism. No country, it was argued, could tolerate having expressly antagonistic and libellous articles written about it. That viewpoint explains how Ronald Farquhart of Reuters became the only British journalist to spend extended periods in Hungary in 1957, until he was replaced in November 1957 by H. A. Gall, the agency's Bonn correspondent

.

But correspondents continued to apply for visas to visit Hungary in 1957 despite the difficulties. Ernest Leiser, a television reporter with CBS, applied for one at the Vienna legation on January 2, but it was refused. He later applied for a visa to make a report on Hungary on April 4, 1958 (then celebrated as Liberation Day), but he was sent away again as he was "very antagonistic in attitude."

Russell Jones was working for UPI in Poland in 1957. His agency wanted to send him to Hungary for two or three weeks, but the Hungarian Foreign Ministry did "not see it as possible" to admit Jones, as "the aforesaid visited Hungary previously during last year's counter-revolutionary uprising, and based on our experiences, he can be counted a persona non grata."

However, he was later admitted after all.

The Hungarian authorities after the revolution sought to admit as few correspondents as possible, to cut the number of antagonistic articles appearing in the Western press, but they could not keep that approach up for long. Quite a number of journalists came to Hungary in 1957 despite the instructions. According to a Foreign Ministry report, 156 journalists from capitalist countries visited in 1957, including 20 journalists and correspondents from Britain

.

The official Hungarian stance on admitting foreign correspondents into the country changed steadily up to 1959. By then the emphasis was on selection rather than a blanket ban. It emerges from archives and confidential diplomatic papers that the applicant's articles on Hungarian subjects would be read and the person judged by the tone of these.

In March 1959, the Hungarian Foreign Ministry approached Sefton Delmer, a celebrated journalist, with an eye to mending bridges with the journalist community. Delmer had previously written sympathetically about the East German question and mentioned in an article that the West German Foreign Ministry was employing some Hungarians connected with the Horthy period and the interwar Christian-Conservative system. Delmer was informed by the requisite Hungarian authorities that the ice had been broken and he was invited to Hungary. He and his wife arrived in the summer of 1959 and he had a chance to interview János Kádár

.

However, there was some kind of blacklist compiled of unacceptables. In October 1959, the authorities organized a two-day protocol excursion for journalists operating in Austria. When the excursion was announced, a confidential list of ten names was also submitted, of correspondents for whom it would not be worthwhile to apply for a visa.

Among the journalists the Foreign Ministry viewed askance was Lajos Léderer of the London Observer, whose work was seen as "anti-government and extremely defamatory." The work of the other Observer correspondent who had been in Budapest in the revolution, George Sherman, was rated no better. He was not even granted a visa after the editor himself, David Astor, had pleaded at the Hungarian Legation on his behalf.

Another name on the blacklist was that of Géza Pogány of the Viennese daily Die Presse. He counted as the foremost "Hungary expert" in the Austrian press. The mission kept him under continual observation and wrote reports on his career for the Foreign Ministry. He made several visa applications, but he was not the bargaining type. In 1963, he paid a visit to the Hungarian Embassy in Vienna with a new application, but did not fail to add that he stood by what he had written previously about the '56 Revolution. He was rejected yet again

.

Some journalists made big efforts to build good relations with Hungarian diplomatic missions. One was Johann Bálványi, who was of Hungarian origin and Vienna correspondent of some Swiss newspapers. Confidential diplomatic reports from Vienna often included gossip about other journalists learned from him. In 1958, he tried to intervene on some colleagues' behalf, arguing the Hungarians "would gain more by admitting such people who had worked a long time in Vienna and made several entry requests, as Helen Anders, Géza Pogány and Bruno Tedeschi."

The state-security services set about reconstructing the events of '56. The interior ministry ordered a six-member committee to be formed to gather and process the material. The result was a group of files marked "The 1956 Hungarian Counter-Revolution in the light of state security work". This had an appendix entitled "More important foreign persons resident in Hungary during the 1956 Counter-Revolution", bearing 160 names

.

It can be assumed that some of the journalists in Hungary during the revolution cooperated with various intelligence services, but the Hungarians appear to have had little accurate information on this. The suspicion typical of the Soviet-type systems meant that every foreigner was seen as a potential spy, but the real spies could not be identified. Some journalists were generally known to have worked for Western intelligence services earlier in their lives. Gordon Shepherd, Vienna correspondent of the Daily Telegraph was a clear example. His obituary in that paper recalled that when Shepherd visited Budapest, the omniscient Rákosi greeted the former MI6 officer with the words, "How goes it, Colonel? How do you like your new job?" Yet the documents of the Hungarian Foreign Ministry and later embassy documents on Shepherd do not refer to him as a suspected spy. He is mentioned simply for the restrained tone of his articles, based on which he was rated positively and recommended for a visa

.

Anthony Cavendish, Warsaw correspondent of UPI, was allowed to visit Hungary for a few days in the summer of 1957 despite his intelligence past in MI6. Only after his arrival did the Hungarians learn that he had meanwhile been expelled from Warsaw. His programme in Hungary was then reorganized to ensure that he could not meet with any official persons. Despite that unfavourable reception, Cavendish managed to return to Hungary again in September 1958.

Anthony Terry, who covered the revolution for the Sunday Times, had also been an MI6 intelligence officer. The Hungarians were probably unaware of this. The London mission rated his articles expressly favourable and objective, and so he was able to visit Budapest again in 1957

.

Seymour Freidin, Vienna correspondent of the New York Post, confessed to being a CIA agent in 1973, and would presumably have been working for US intelligence in 1956 as well. There is no trace of such a suspicion in any Hungarian document.

* * * * *

The foreign correspondents working in Hungary during the '56 Revolution played an important part in making the events known worldwide. There was no other occasion in the 20th century when world attention and sympathy turned to Hungary to such an extent as in October 1956.

The names of most correspondents have sunk into oblivion in Hungary. This study attempts to revive the memories of some of them. In some cases, they would gain fame in other walks of life and become well known in their own countries. Many of them are still alive.

For a few, such as Peter Fryer, who broke with the British communist party, the short period spent in Budapest was a turning point in their lives. Some among them spent a lifetime travelling from one crisis area to the next, so that the events in Hungary seemed a fleeting episode to them. But apart from a few pro-Soviets, they sympathized with the Hungarians, students and workers who took up arms and did not want to live under a Soviet yoke any more.

The journalists sensed with the citizens of Hungary the greatness of those days of revolution and the tragedy of the defeat. As Russell Jones put it in his Pulitzer Prize-winning series of articles, "Life as the only American correspondent left in shattered Budapest is sometimes frightening, sometimes amusing. But mostly it is a continuous feeling of inadequacy both as an American and as a reporter who helplessly watched the murder of a people. For the first time since I was a boy I wept."

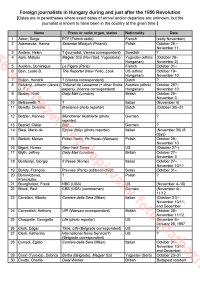

Foreign journalists in Hungary during and just after the 1956 Revolution

|

| Foreign journalists in Hungary during and just after the 1956 Revolution. Page 1

-* |

|

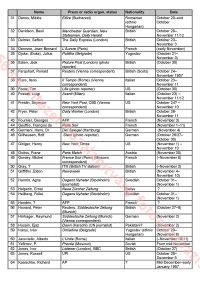

| Foreign journalists in Hungary during and just after the 1956 Revolution. Page 2 -* |

|

|

|

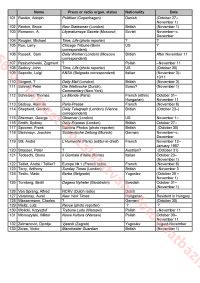

| Foreign journalists in Hungary during and just after the 1956 Revolution. Page 3 -* |

|

| Foreign journalists in Hungary during and just after the 1956 Revolution. Page 4 -* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Copyright © 2007 The Institute for the History of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution – credits |

|

|